Almost 8% of U.S. homes sold in 2023 exceeded the capital gains tax limit of $500,000

The 2024 tax season officially ended earlier this week, with the IRS expecting Americans to file more than 146 million returns. It is this time of the year that many homeowners who sold their properties during the previous year will enjoy a significant tax benefit on their homeownership investment.

Since 1997, homeowners can exclude housing capital gains for up to $500,000 (or $250,000 for a single filer) when they sell their houses. [1] For anything below the exemption limit, homeowners do not even need to report the sale to the IRS.

But with skyrocketing home prices during 2021 and 2022, a growing number of homeowners are finding for the first time that they may owe taxes on excess capital gains beyond the exemption limits. This is because their property values have doubled, tripled or even quadrupled over the years since they bought the home.

More Home Sales Are Topping the Capital Gains Exemption Limit

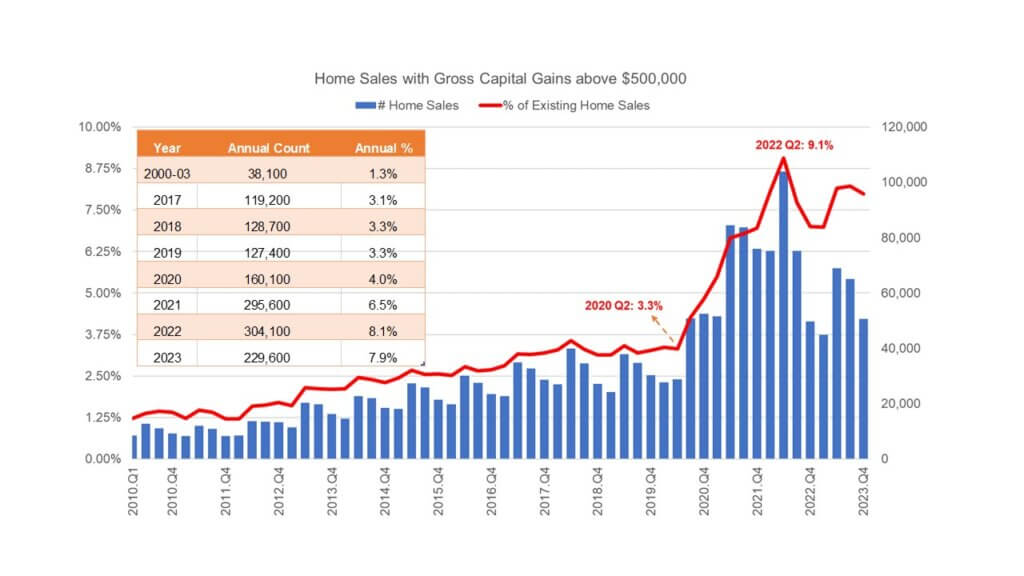

The tabulations in Figure 1 are based on gross housing capital gains. The actual numbers will be lower than shown, as homeowners can deduct eligible costs and expenses from taxable gains when buying, selling and improving properties.

In the decade before the pandemic fueled the housing frenzy, a rather small number of home sales had the kind of gross capital gains that could put homeowners over the exemption threshold. Between 2000 and 2003, a few years after the passage of The Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997, only about 38,000 home sales per year, or 1.3% of existing home sales, had gross capital gains that exceeded the exemption limit. In 2017, 2018 and 2019, a period when the housing market was on a steady upward climb, the numbers hovered at below 130,000 annually and represented about 3% of annual existing home sales.

But that changed a couple of years ago as home prices surged sharply. In the peak year of 2022, more than 300,000 home sales had gross capital gains above the $500,000 exemption limit, a staggering 140% increase from pre-pandemic levels. In Q2 2022, when home price acceleration rose to the pandemic-cycle peak, sales of homes that exceeded the capital gains limit reached 9.1% of quarterly existing home sales. In 2023, these sales dropped by 25% from 2022 to slightly shy of 230,000 but were nevertheless up by 80% from 2019. At the end of 2023, home sales that required capital gains payments stood at 7.9%, 150% higher than the 2017-2019 average.

A Significant Number of Long-Term Homeowners in High-Cost Areas Might Be on the Hook for Capital Gains Taxes

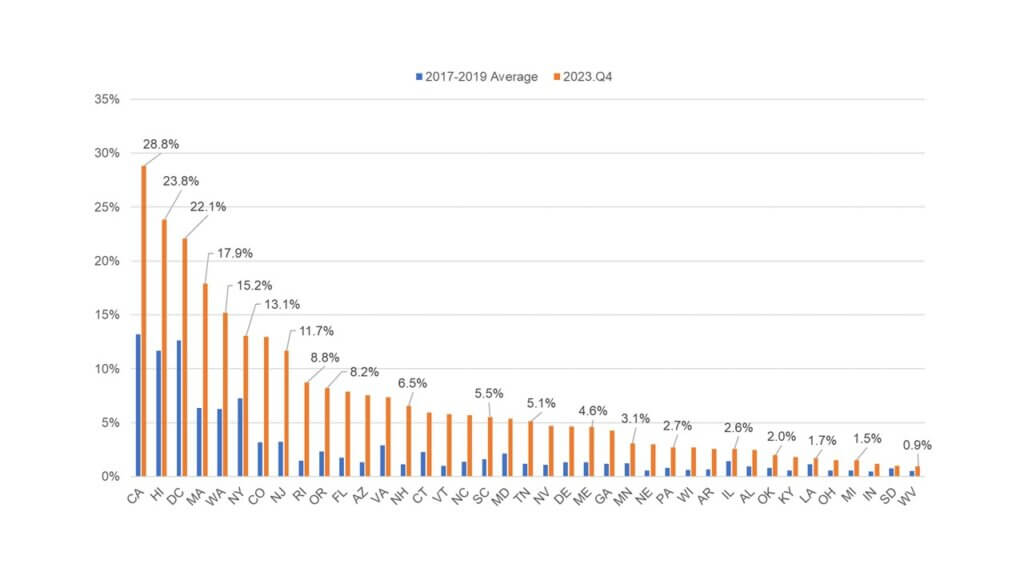

At the state level, long-term homeowners in high-cost areas are expected to carry the lion’s share of homes that owe significant capital gains payments. That is because in dollar terms, high prices equal higher amounts of capital gains if given the same rate of home price growth, not to mention that many high-priced areas are frequently among the fastest-appreciating markets.

Take California, for example. Between 2017 and 2023, the Golden State alone accounted for 37% of national sales that had gross capital gains beyond the exemption limit. During the same period, California’s overall existing home sales made up a much smaller portion (10%) of the national overall volume.

Five other expensive states accounted for 31% of sales nationwide that had gross capital gains above the exemption limit: New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts, Florida and Colorado. Along with California, these states had a combined total of 68% of national sales that had gross capital gains above the exemption limit. (For reference, their combined overall existing home sales made up 35.5% of national sales between 2017 and 2023.)

Figure 2 shows that exemption-exceeding housing capital gains have become more common in many high-cost states, led by California. At the end of 2023, California recorded 28.8% of existing home sales with gross capital gains above $500,000. Hawaii and Washington, D.C. followed, with 23.8% and 22.1% shares, respectively.

Double-digit exemption-exceeding sales were recorded in Massachusetts (17.9%), Washington (15.2%), New York (13.1%), Colorado (13%) and New Jersey (11.7%). States with sales in high single digits (at or above the national average) include Rhode Island (8.8%), Oregon (8.2%) and Florida (7.9%). By contrast, before the pandemic, exemption-breaking home sales registered 13.2% in California; 12.6% in Washington, D.C.; 11.7% in Hawaii; 7.3% in New York; 6.4% in Massachusetts; 6.3% in Washington and 3.2% in both Colorado and New Jersey.

What does this trend mean for homeowners in states like California, where nearly three in 10 recent home sales have approached the exemption limit? For one thing, it means owing capital gains taxes upon selling homes has become more common than it was when The Taxpayer Relief Act became effective. Then, very few homes — except for multimillion-dollar properties owned by high-income, high net-worth individuals — could generate the kind of large capital gains that would push them beyond the tax limits. Nearly 30 years later, even modest homes for average-income families in many high-cost markets routinely sell for more than $1 million.

Capital Gains Exemptions Are Not Adjusted for Inflation

Since 1997, capital gains exemptions on housing have not kept up with inflation or the cost of living. This is unlike many other federal tax provisions, such as the standard deduction or the income tax credit, which have annual inflation-adjustment provisions.

In this time, the cost of living as indicated by the Consumer Price Index has nearly doubled, while average home prices have more than tripled (around the multiple of 3.6) and likely soon to quadruple given current appreciation trends. In other words, when adjusted for inflation, the exemption provision, which was worth $500,000 ($250,000 for a single filer) in 1997, has an inflation-adjusted value of $262,000 (or $131,000) in today’s dollar. [2]

With high mortgage rates and housing costs challenging housing affordability for millions of households, owing capital gains taxes can be an unexpected (and unwelcome) surprise for long-term owners who are in the process of selling their home while trying to purchase another.

For more recent CoreLogic coverage regarding property taxes, check out this March blog post on the most expensive U.S. places for annual property taxes, as well as this February analysis on tax increases since the pandemic. And you can always find the latest insights from our team of expert housing economists at this home page.

[1] To qualify for the exemptions, homeowners must have owned and used the house as primary residence for a minimum of two years out of the past five years before selling the house.

[2] The presence of outstanding mortgage(s) on a house does not affect the calculation of capital gains or taxes owed on taxable gains. The owners will use the proceeds from the sale to pay off the mortgage(s).